'Hot Water' Review: A Road Trip Through Impossible Choices

by Kathia Woods

There's something deeply human about watching Layal methodically peel and eat oranges throughout her cross-country drive with her teenage son. She's trying to quit smoking, but as Syrian-American filmmaker Ramzi Bashour reveals in his feature debut

Hot Water: Those oranges aren't just about nicotine withdrawal—they're a physical manifestation of the impossible weight this Lebanese immigrant mother is carrying. Her son Daniel thinks she's just wound too tight and that quitting smoking is making her tense. He has no idea that while he's struggling through his crisis in America, Layal's mother back in Lebanon has just had an accident. She's caught between two worlds, two urgent needs, thousands of miles apart. And there's no right answer.

Azabal Anchors with Sarcasm and Soul

Lubna Azabal, best known for her Oscar-nominated work in Paradise Now and Incendies, delivers a performance that feels instantly recognizable to anyone who's known an immigrant parent juggling professional ambitions with family obligations across continents. As Layal, an Arabic professor at an Indiana college, Azabal brings a sharp, sardonic wit that makes her character utterly relatable. Her sarcasm isn't meanness—it's armor, a coping mechanism for someone who feels like she's failing on multiple fronts.

The film kicks off after Daniel (Daniel Zolghadri, continuing his streak of playing deadpan troubled teens) gets expelled from high school following a violent hockey incident. Layal's solution? Drive him across the country from Indiana to California to live with his estranged father, Anton—a man whose addiction problems are mentioned but frustratingly never explored in depth.

The American West as Mirror and Canvas

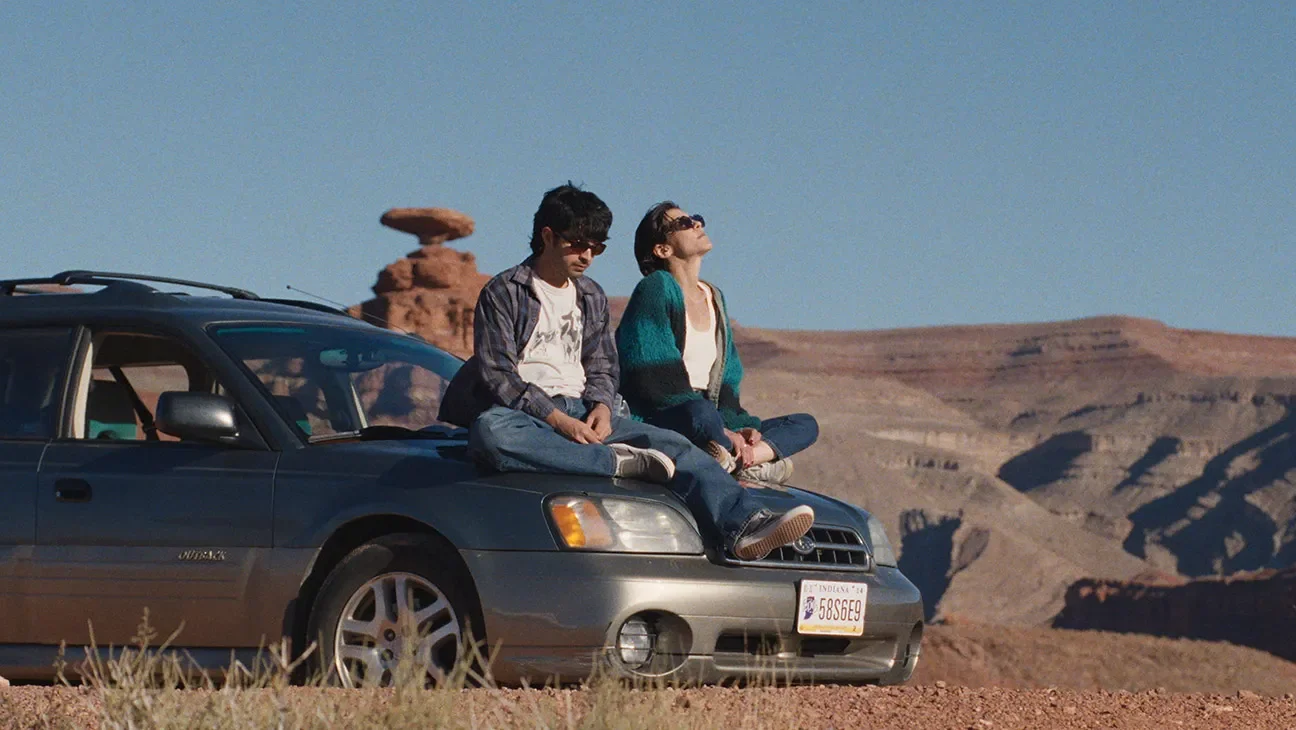

Cinematographer Alfonso Herrera Salcedo (A Love Song) does beautiful work capturing the transition from Midwest to West—the landscape gradually opening up as mother and son navigate their cramped emotional space inside the car. There's a visual poetry in the contrast: these sweeping vistas of American possibility against the claustrophobic reality of Layal's impossible situation. She can't be in two places at once; she can't tend to her aging mother while also shepherding her troubled son through this crisis.

Humor and Humanity in the Mundane

What sets Hot Water apart from typical road-trip dramedies is its commitment to finding genuine humor in the everyday friction between this mother and son. Their fighting seems real—she makes fun of his bad Arabic, and he irritates her because he can. These aren't grand dramatic showdowns; they're the small tensions that define real family relationships. The film smartly avoids turning their Lebanese Muslim identity into trauma porn.

Instead, it shows them as a normal family going through common problems: a kid who has lost his way and a parent who is trying to help him while dealing with her own grief and guilt.

The film's multilingual elements, with Layal easily switching between English, Arabic, and French, add depth without making it look like a show. This is just how she moves through the world, switching languages and cultures as needed, never fully fitting into any one group.

The Missing Father

The biggest criticism of Hot Water is its treatment of Anton, Daniel's father. While the story rightly centers on the mother-son dynamic, Anton exists primarily as a destination rather than a fully realized character. We're told he has an addiction problem, that his absence has shaped Daniel's life, but the film never inquires about how this separation has actually affected Daniel emotionally. For a movie about driving a teenage boy across the country to reunite with his estranged father, that feels like a significant missed opportunity to explore another layer of Daniel's struggle.

The Grace of Not Knowing

What ultimately makes Bashour's debut resonate is its refusal to offer easy answers.

Hot Water understands that for many immigrants—and their children—the question of belonging isn't something you solve; it's something you live with. Layal doesn't know if she made the right choice staying in America instead of returning to Lebanon. She doesn't know if she's doing right by Daniel or failing him. The film suggests that maybe the first step toward finding your place is admitting you don't know where you belong yet. And that's okay.

In an industry that too often demands tidy resolutions and clear character arcs,

The film sits comfortably with ambiguity. It's a road movie where the destination matters less than the conversation happening in the front seat—two people trying to understand each other across generational and cultural divides, one orange peel at a time.

It is a warm, thoughtful debut that offers a refreshingly normal portrayal of a Muslim Lebanese-American family while grappling with the universal immigrant experience of being split between worlds. Anchored by Lubna Azabal's magnificent performance and Bashour's gentle directorial hand, it's a film that trusts its audience to sit with life's messiness. Just don't expect all the answers—sometimes the journey is about learning to be okay with the questions.